When I Can Read My Title Clear

Literacy, Identity, and Voting

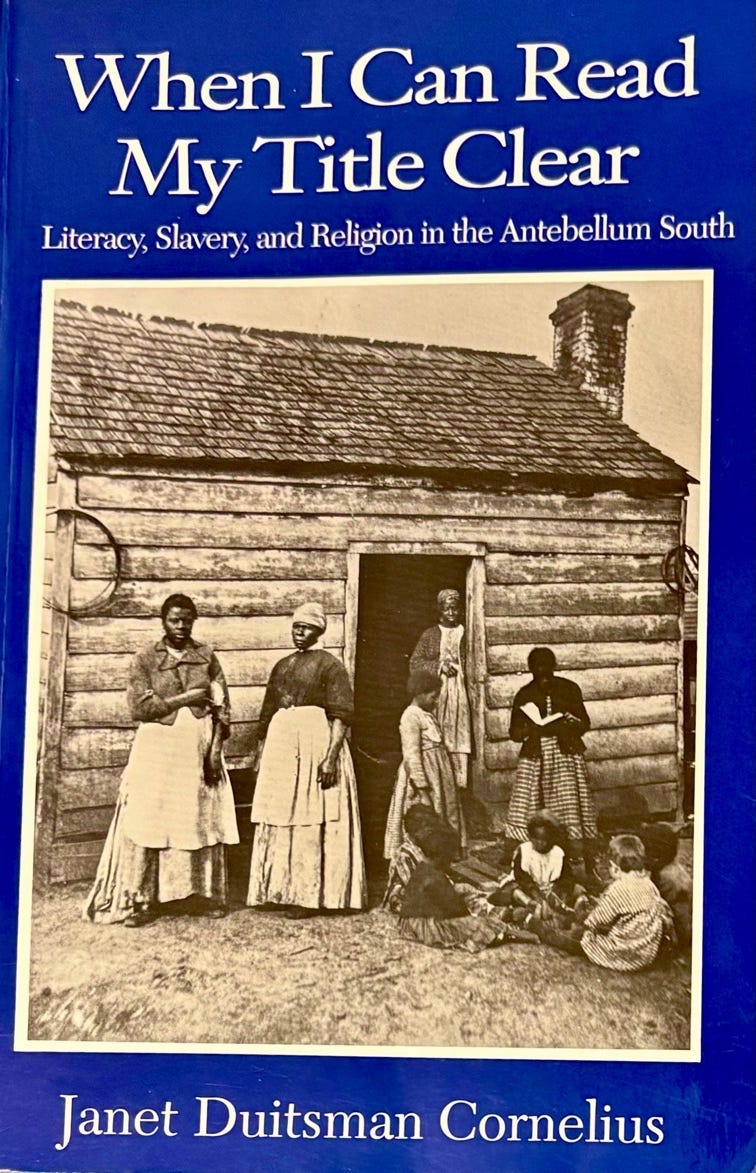

Whenever I see this book, “When I Can Read My Title Clear: Literacy, Slavery, and Religion in the Antebellum South (WICR),” I think of enslaved and free people. I think of my 2nd great grandparents who could read but not write, who were free and of African and Native American descent--Cherokee and Cree. They experienced the same or similar negative treatment/restrictions as enslaved people.

They understood the benefits of literacy. They would also have subscribed to James Olney’s thoughts as expressed in WICR:

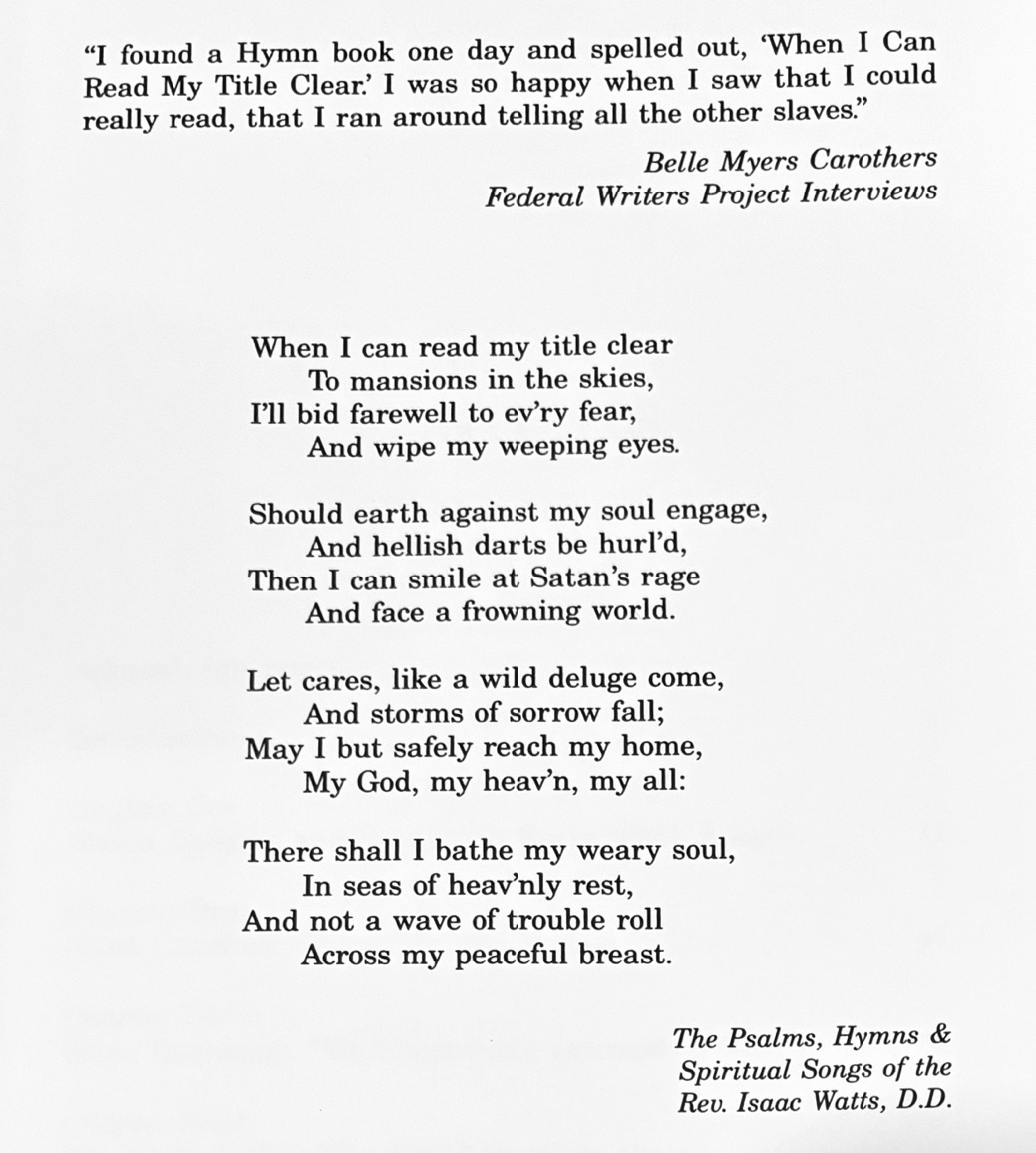

literacy was a mechanism for forming identity, the freedom to become a person;

Olney, quoting Frederick Douglass’s pronouncement at the end of his biography stated — “that lettered utterance is assertion of identity and in identity is freedom—freedom from slavery, freedom from ignorance, freedom from non-being, freedom even from time,” since “writing endures beyond a moment or even beyond a lifetime.” p. 2

While my 2nd great grandparents were only partially literate (Their marriage certificate suggest they could read but not write in 1867, signing their Certificate with an “X.”. It’s hard for me to believe they didn’t learn to write before their children were born or at least during the raising of the children given what they and their children accomplished. However, they voted in 1867 and signed the ballot with and “X.”

They knew it was critical that their children were literate. Their son, my great grandfather, Willie, was literate and an entrepreneur. His children followed in his footsteps, becoming literate and skilled crafts women—he had all girls. My grandmother was one of them.

It’s 2023, almost 2024, and some people in America aspire to go back to the 1940s and 1950s—a horrific time of continued hangings, segregation, extreme racism, and intolerance.

High rates of illiteracy continue in America in marginalized communities even though people of African descent have gave it priority since enslavement. Note the beginning of WICR

I highlighted much of the book when I first read it. It answered so many questions for me; and, led to questions I asked of my grandaunts. I wanted to ask them of my grandmother, but she transitioned many years before the book was published. This quote in particular sums up the way I understood grandmother, her siblings, and the others with whom they’d grown up with—neighbors, friends, other family members— thought of literacy:

Instruction is the great want of the colored race, it needs the light, ideas, facts, principles of action, for its development and progress. In this armor alone can it fight its battles, and secure its rights, and protect its interest amid the forces of civilization. p.83

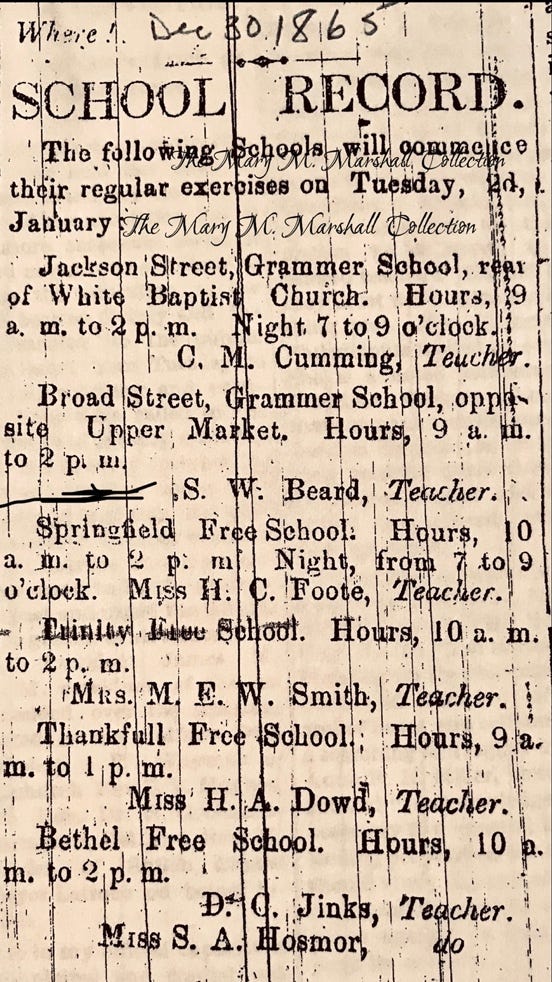

Seeking literacy and the right to vote was not new to Black Americans. In the South, Black Georgians were among the first to lead the way in education. On Dec. 30, 1865, 6 schools were already operating in Augusta, GA. My family’s beloved Springfield Baptist Church (SBC) was one of them. Black Georgians, of all ages, from Augusta and the surrounding CSRA (Central Savannah River Area) attended.